When addressing content accessibility in courses or websites, what do you do with a video that you don’t own? In my experience building out our faculty development website, iTeachU, and in augmenting courses to be fully accessible, I have learned a few tricks. I’ll share these here!

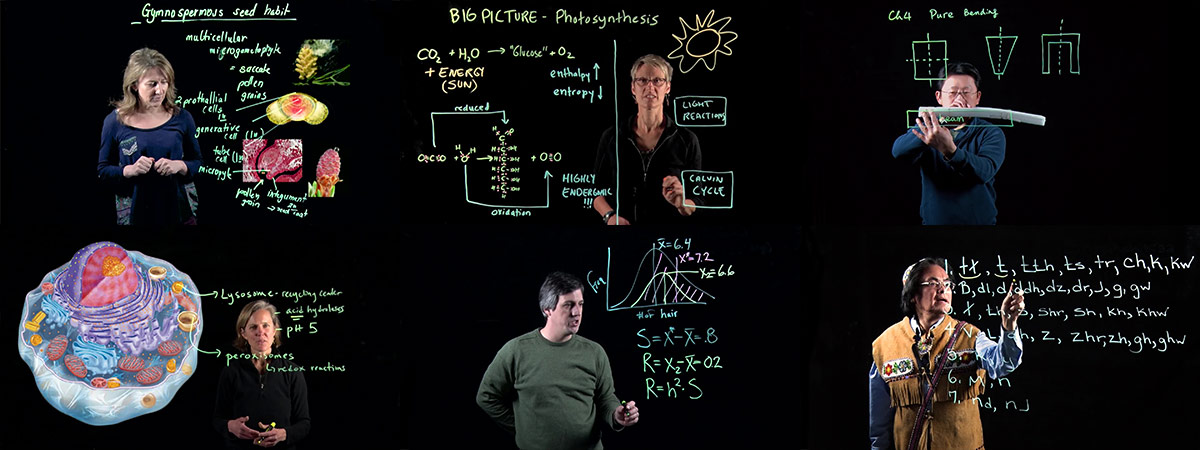

First, let me just say that you should always caption your own content. UAF eCampus captions by default all content that we produce and that is produced in partnership with us. UA has an institutional pricing agreement through a third party vendor, 3Play Media. We also make use of other third party services such as GoTranscript, Trint, and Verbit.ai depending on the turnaround time needed, nature of the video content, amount of captioning required, and other factors.

YouTube

If the video lives in YouTube, you might luck out and be able to contribute captions to the video directly. YouTube has a feature known as community contributions, which allows anyone to submit captions or subtitles in any language. This is not on by default for videos or channels (please go to your channel now and turn them on!), so this isn’t as common as would be preferable. In reviewing third party video content on iTeachU, at least one video had community contributions turned on. This allowed us to add captions that we paid to have created, wait for it to be approved by the video owner, and leave the embed intact. One particularly important video, however, did not anything other than YouTube’s autocaptions. I attempted to contact the creator of the video to ask him to turn on community contributions, but given the complexity of his email how-to webpage, and his lack of response, we had to figure out how to add our own accurate captions to the video.

The broad solution is to find a way to rewrap the video in an external player that can serve the video from its YouTube source, but inject captions separately. This allows you to not touch the video or its copyright, but apply your own captions to it. This doesn’t require permission or any privileged access.

There are three specific solutions that I have found:

Kaltura MediaSpace

This, currently, is our preferred solution. The UA-wide installation of Kaltura allows users to add a YouTube video as an entry in Kaltura itself, while still serving the video from YouTube. These videos must be public or unlisted (Kaltura’s instructions specify public videos, but unlisted videos will work). Once you have your caption file created for the original video, you simply upload the caption file to the new Kaltura entry for the video and it will play back in the Kaltura player:

PlayPosit

PlayPosit does effectively the same thing as Kaltura Mediaspace. It rewraps the video stream in another player that can display captions that you add manually. This is a bit of a workaround, because PlayPosit is designed to add interactivity to the video. It also could introduce some confusion to the viewer, since the video is presented as something more than a video, and without actual additional interactive elements, folks might be a little flummoxed. But it works, and this is accessible to anyone using PlayPosit, even the free tier.

Amara

Amara is a free, open-source tool for creating captions for video content. It also allows you to add captions to a third party video in YouTube and will give you an embed code that can be added to a website. It does require Javascript and the embed code required some tweaking to display properly here in WordPress (the <div> size had to be manually set to allow the embed to appear properly (by adding style=”height: 360px;” to the div tag). But it does work.

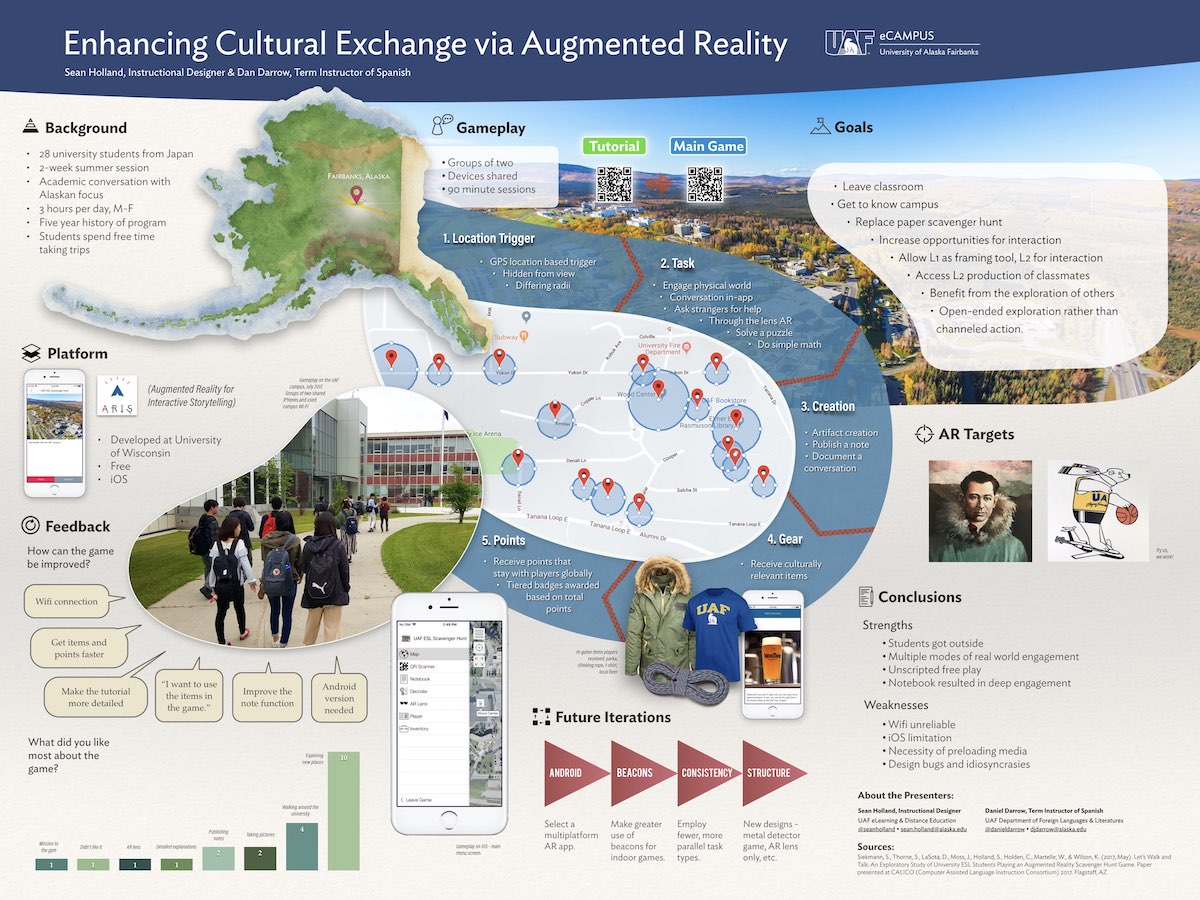

I used Keynote to design the poster after sketching it out roughly by hand. I have used Keynote before to do things that require a lot of visual elements, and I was pleased that I didn’t have to make any serious compromises or devise any major workarounds to create the design I wanted. It was very useful to work on the presentation on a large 5K iMac monitor, although I also did a fair amount of work while in a cramped coach airplane seat.

I used Keynote to design the poster after sketching it out roughly by hand. I have used Keynote before to do things that require a lot of visual elements, and I was pleased that I didn’t have to make any serious compromises or devise any major workarounds to create the design I wanted. It was very useful to work on the presentation on a large 5K iMac monitor, although I also did a fair amount of work while in a cramped coach airplane seat.